My bookshelves and never-ending lists of books to read are mostly comprised of writers who are old(ish) or dead. This arises partly from my education, having studied English at university and devouring the work of Atwood, Joyce and Swift. Even during high school, the colonial influence of our country’s past meant we were reading the work of old, dead guys like Dickens and Golding. I am happy to hear that my cousins who are in school now are being prescribed South African books as well, but I have a deep love and appreciation for the “classics” nevertheless and there is no denying the profound veracity of their themes.

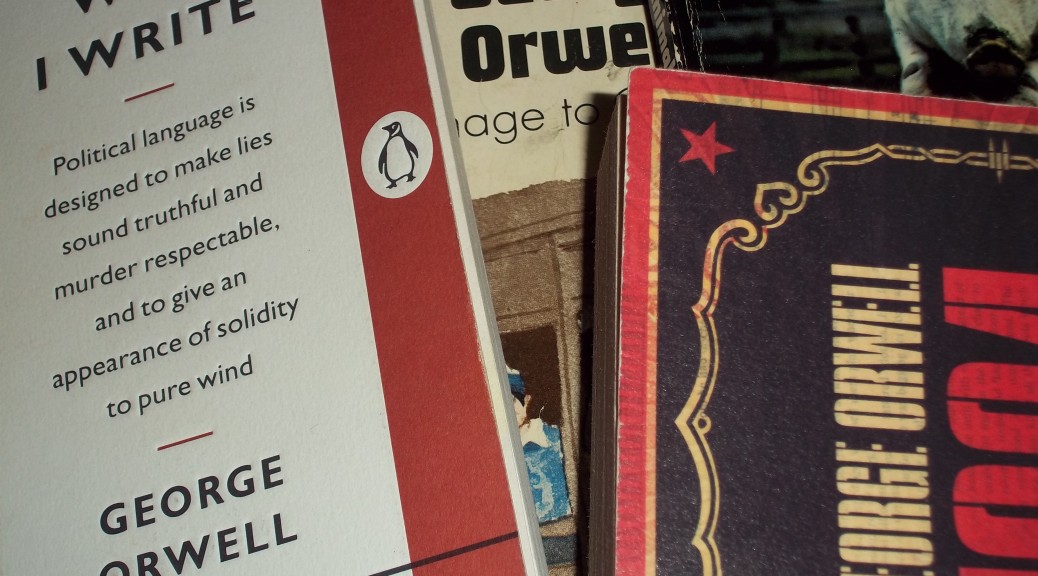

But I digress. I was trying to make a point about dead writers, and the books that stand on my shelves like eternal epitaphs to their masters. One of these is George Orwell. His writing never formed part of my set works, but as he is a classic, literary daisy-pusher, he makes my point. Not that I have much of a point to make other than to celebrate the work of this great writer on what would have been his 111th birthday, starting simply with his writing rules which have helped me with my own work:

i. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

ii. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

iii. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

iv. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

v. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English alternative.

vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

One of the things I love about reading books written decades or centuries ago is the eerie prophesy contained in many of the stories and themes. Nineteen Eighty-Four stands as a good example. Even though our world today is not quite the Orwellian dystopia found in the novel, a lot of its situations, particularly the death of privacy, are relatable and true on some level, as evidenced by some of these quotes:

• For it is only by reconciling contradictions that power can be retained indefinitely.

• Being in a minority, even a minority of one, did not make you mad.

• There was a direct, intimate connection between chastity and political orthodoxy. For how could the fear, the hatred and the lunatic credulity which the Party needed in its members be kept at the right pitch, except by bottling down some powerful instinct and using it as a driving force? The sex impulse was dangerous to the Party, and the party had turned it to account.

• In the past no government had the power to keep its citizens under constant surveillance. The invention of print, however, made it easier to manipulate public opinion, and the film and the radio carried the process further. With the development of television, and the technical advance which made it possible to receive and transmit simultaneously on the same instrument, private life came to an end. Every citizen, or at least every citizen important enough to be worth watching, could be kept for twenty-four hours a day under the eyes of the police and in the sound of official propaganda, with all other channels of communication closed. The possibility of enforcing not only complete obedience to the will of the State, but complete uniformity on all subjects, now existed for the first time.

Published in 1949 the book was banned in the Soviet Union in 1950. Animal Farm was also banned in the Soviet Union, and is still banned to this day in Cuba and North Korea. It is frightening to realise that books are still banned today, but also reaffirms the power that words and ideas have, something Orwell strongly believed in.

In Memorian, George Orwell, 1903 – 1950